Samuel Beckett and Tom F. Driver on the Function of Art in a World in Crisis

There is so much about my work as an artist that is changing. Much of what interested me just three years ago feels frivolous now. I stopped writing a romantic comedy just before Trump was elected and I’m not sure I could summon the drive to finish it now regardless of what someone offered to pay me.

What I’m drawn to write about is different. What I’m drawn to watch on TV or in the theater is different. And it’s the same with everyone I meet. This world reckoning isn’t just happening on the macro level. The shift is happening within as well.

As above, so below.

How do we evolve as artists? How do we create art that reflects and brings meaning to a shifting, chaotic world? Samuel Beckett has some ideas. The groundbreaking, post-WWII playwright wrote for a deeply traumatized culture coping with the loss of 70 million lives and wrestling with the anxiety of a newly Nuclear Age. I recently stumbled on a fascinating article on Beckett by theologian Tom F. Driver. In 1961, at a Paris cafe next to the Madeleine Church, Driver questioned Beckett on the function of art in a shifting, chaotic world. His answers, as well as Driver’s observations, speak directly to our current moment.

Driver: Beckett would often call what he saw happening in the culture as “the mess,” or sometimes “this buzzing confusion.”

The confusion is not my invention. We cannot listen to a conversation for five minutes without being acutely aware of the confusion. It is all around us and our only chance now is to let it in. The only chance of renovation is to open our eyes and see the mess. It is not a mess you can make sense of.

Driver: Then he began to speak about the tension in art between the mess and form. Until recently, art has withstood the pressure of chaotic things. It has held them at bay. It realized that to admit them was to jeopardize form. “How could the mess be admitted, because it appears to be the very opposite of form and therefore destructive of the very thing that art holds itself to be?” But now can we keep it out no longer, because we have come into a time when “it invades our experience at every moment. It is there and it must be allowed in.”

What I am saying does not mean that there will henceforth be no form in art. It only means that there will be new form, and that this form will be of such a type that it admits the chaos and does not try to say that the chaos is really something else. The form and the chaos remain separate. The latter is not reduced to the former. That is why the form itself becomes a preoccupation, because it exists as a problem separate from the material it accommodates. To find a form that accommodates the mess, that is the task of the artist now.

Driver: Yet, I responded, could not similar things be said about the art of the past?… Isn’t all art ambiguous?

Driver: “Not this,” he said, and gestured toward the Madeleine. The classical lines of the church, which Napoleon thought of as a Temple of Glory, dominated all the scene where we sat. The Boulevard de la Madeleine, the Boulevard Malesherbes, and the Rue Royale ran to it with a graceful flattery, bearing tidings of the Age of Reason.

Not this. This is clear. This does not allow the mystery to invade us. With classical art, all is settled. But it is different at Chartres. There is the unexplainable, and there art raises questions that it does not attempt to answer.

Driver: I asked about the battle between life and death in his plays. Is this life-death question a part of the chaos?

Yes. If life and death did not both present themselves to us, there would be no inscrutability. If there were only darkness, all would be clear. It is because there is not only darkness but also light that our situation becomes inexplicable…. Where we have both dark and light we have also the inexplicable. The key word in my plays is ‘perhaps.’

At a party an English intellectual—so-called—asked me why I write about distress. As if it were perverse to do so! He wanted to know if my father had beaten me or my mother had run away from home to give me an unhappy childhood. I told him no, that I had had a very happy childhood. Then he thought me more perverse than ever. I left the party as soon as possible and got into a taxi. On the glass partition between me and the driver were three signs: one asked for help for the blind, another, help for the orphans, and the third for relief for the war refugees. One does not have to look for distress. It is screaming at you even in the taxis of London.

Driver: In the Beckett plays, time does not go forward. We are always at the end, where events repeat themselves (Waiting for Godot), or hover at the edge of nothingness (Endgame), or turn back to the long-ago moment of genuine life (Krapp’s Last Tape). This retreat from action may disappoint those of us who believe that the events of the objective world must still be dealt with. To say “perhaps,” as the plays do, is not to say “no.” The plays do not say that there is no future but that we do not see it, have no confidence about it, and approach it hopelessly.

This last point by Driver feels especially apropos today. (With the instability brought on by our current world leadership as well as the worsening climate crisis, the future has never looked so uncertain.) He goes on to theorize as to why Beckett’s plays were (and, incidentally, still are) so vexing for some audiences. (emphasis my own)

Driver: The walls that surround the characters of Beckett’s plays are not walls that nature and history have built irrespective of the decisions of men. They are the walls of one’s own attitude toward his situation. The plays are themselves evidence of a human capacity to see one’s situation and by that very fact to transcend it. That is why Beckett can say that letting in “the mess” may bring with it a “chance of renovation.”

Driver: Is it not true that self-transcendence implies freedom, and that freedom is either the most glorious or the most terrifying of facts, depending on the vigor of the spirit that contemplates it? It is important to notice that the rebukes to Beckett’s “despair” have mostly come from the dogmatists of humanist liberalism, who here reveal, as so often they do, that they desire the reassurance of certainty more than they love freedom. Having recognized that to live is not enough, they wish to fasten down in dogma the way that life ought to be lived. Beckett suggests something more free—that life is to be seen, to be talked about, and that the way it is to be lived cannot be stated unambiguously but must come as a response to that which one encounters in “the mess.” He has devised his works in such a way that those who comment upon them actually comment upon themselves. One cannot say, “Beckett has said so and so,” for Beckett has said, “Perhaps.” If the critics and the public see only images of despair, one can only deduce that they are themselves despairing.

For all of you artists out there or anyone trying to make sense of things as well as your place in things, there is deep wisdom here. We cannot avoid the predicament in which we find ourselves. We cannot bury our heads in the sand. Nor can we make art that attempts to “fasten down in dogma”. We must make art that “allows the mystery to invade us”. We must let the mess in.

Full transcribed interview here.

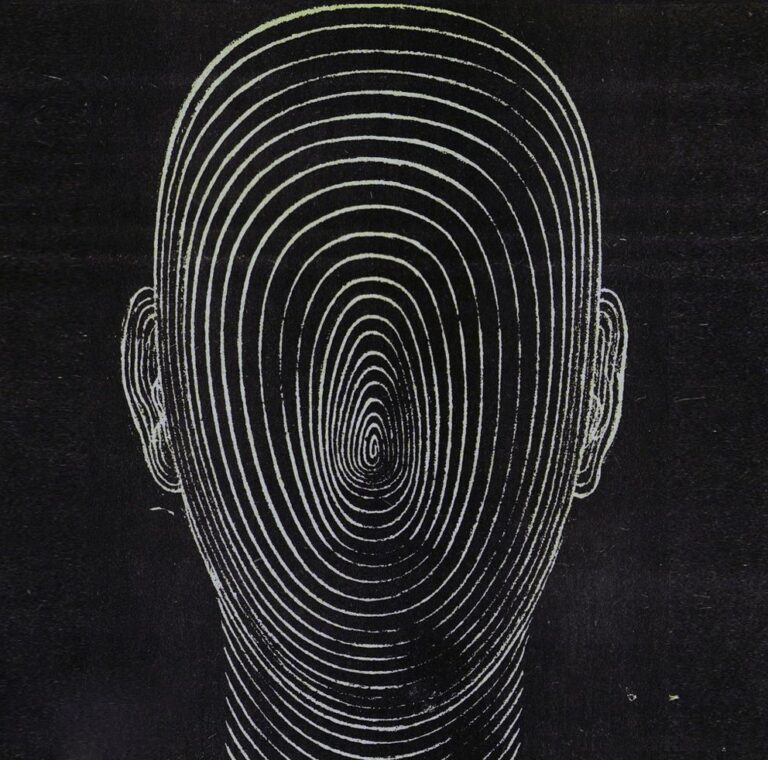

Image: Francis O’Connor’s set design for Druid Production Company’s 2017 production of “Waiting for Godot”